|

NOTES ON THE HISTORY OF TSINTZINA ©: S.N.A., 2007 Contents:

1.

timeline

3. MYTH,

FACT AND ANECDOTAL EVIDENCE 1. Introduction: The Early Misconceptions Initial interest in Tsintzina history and folk, dates to the late 1910s. Posts on the subject started by two nonTsintzinians:

Above left: Agissilaos Sgouritsas, right: Professor Phaedon Koukoulės, In the early to mid 1920s, Sgouritsas was editor of “Malevos” magazine. “Malevos” was a rather lively publication, dedicated on tradition and current affairs of South Mt. Parnon villages. His cooperation with Koukoules produced several Tsintzina articles. Some of them –and several others based on their assumptions- later appeared at a string of US Tsintzina Association’s Annual Convention Yearbooks, between the 1920s and the 1950s. Sgouritsas and Koukoules should be praised for discovering several facts and for structuring some well-articulated hypotheses. Equally, it must be acknowledged that often, their articles contained misconceptions and inaccuracies. Perhaps the greatest of them was on the origin of the name “Tsintzina”. Such erroneous conclusions or statements were largely the –often unavoidable- product of manner of research and methodology, improper or misleading correlation with broader historical developments or simply, being driven by the wrong assumption. It was never-the-less a praiseworthy and pioneering effort, given the limited means and recourses of that time. Since the 1930s, Tsintzina history debate continued in the Jamestown Lefkomata. In 1961, the launch of John (Motivo) Andritsakis’s “TA TSINTZINA” newspaper took over. Between 1960-56, it aired some real scholarly work, of noteworthy contributors such as Thanos Vagenas and Dimitri Kallianis (both nonTsintzinian). After

Motivo’s death in 1980, the newspaper continued for another 23 years

mostly by the Tsintzina Athens association. This period, some

Tsintzinians published noteworthy news and facts from time to time.

They included Panos Gerasimos, Panos Doscas, Spiros Andritsakis and

Dimitris Giannoukos. Giannoukos has also published a short book in

2006, on aspects of Zoupena history, dealing occasionally with

Tsintzina. 2. What of Tsintzina before the Imperial Decree of 1292 The first written reference on Tsintzina appears on a Byzantine Imperial decree of 1292. There, Emperor Andronicus Paleologos finishes important administrative arrangements in south Peloponnese, after the Byzantines recaptured the area from the Franks. The Byzantines were often far from ideal rulers for Southern Greece. Their leaders and officials frequently called this part of the world as “topon mychaition” , a derogatory way of referring to an “inferior” land. This, atop a heavy taxation and evidence of a significant draft quota, occasionally made the Byzantines look like rather unwelcome tyrants. It is not surprising therefore that local people seemed to have reached a modus vivendi with the Franks in their 13th century conquest of South Greece. Byzantine recapturing of the area was resisted by the Tsakones in particular. Perhaps the only significant Byzantine ally in the vicinity was the Monemvassia authorities. The Decree, reflects part of their reward after the area was recaptured. In the Decree itself, it is not entirely clear if “Tsintzina” refers to a village or merely, area. We may not be entirely sure if we have an organized habitation until the other Byzantine Decree of 1416. There, the penultimate Byzantine Emperor Theodore II Paleologos, specifies details about taxation levied on the people of Tsintzina (and of other nearby villages). Some have suggested a Tsintzina habitation as early as the 9th century AD. At that time, Byzantine Emperor Nicephorus fought steadily to consolidate Imperial hold in South Peloponnese. It is possible therefore that local populations sought refuge in the mountains from the invading Imperial Army. It has been suggested that the existence of a nearby hill called “Katafi” or properly “katafigio”, which in Greek means “refuge” or “shelter”, is connected with these developments. The same has been suggested for the several caves below Katafi” . The best known of them is St. John’s cave, overlooking the village from a steep and naturally fortified position eastward. In its top, a very old chapel exists, dedicated to St. John the Baptist. Some articles posted in the past, have suggested that its wall-painted icons had an inscription of 1333. This may not annul the possibility of the chapel being much older. One strong advocate of this theory is Constantine Psichogios, in his unpublished Monograph of 1941. In fact, he seems certain that people sought shelter in places like “Katafi” a good deal earlier. Psichogios connects habitation in the nearbies, back to at least the era of the devastating Alarichos raids which destroyed ancient Sparta in the 4th Century A.D. His other claim about a much earlier settlement in the nearby Karyia plateau, has yet to be supported by remnants or other evidence. In his book about the history of Verroia (a village some 4 miles west of Tsintzina), Dimitrios Koufos has suggested similar small settlements in at least two places close to Tsintzina on the west, called “Kartsia” and “Elliniko”. Like Psichogios, Koufos also claims some remnants which are probably not visible today. The above remain interesting suggestions. They may not yield anything, unless a proper archaeological search is ever conducted. There are two solid facts however: An old building, perhaps dating back to at least the Hellenistic period, does in fact exist in Marmara. This location rests just off the road to Vamvakou, some 5 miles Northwest of Tsintzina village. Its remnants are still visible, although largely destroyed when the road was widened and tarred in the 1980s. Koufos has measured this building and gives a width of some 9ft and a length of some 16 ft (2,80m x 5,90m). He then cites several possibilities, including a 1903 paper by Sgouritsas, where he claims that most probably it was a commemorating structure. Secondly, in the early 1990s Tsintzinians became perplexed when torrential rains in winter washed-off three tomb-shape graves above St Nicholas chapel, in the NW end of the village. It is not clear if the Archaeology Department visited the site and what was their report. This incident has now largely been forgotten. Finally, in a

2006 book on Zoupena, Dimitri Giannoukos makes one interesting

suggestion. Tsintzina, he says, were probably included in the domain

of the Melissinos family possessions, during the Frankish Conquest

(12th – 13th Century). This could be

possible on account that the Melissinoi at one point were the

feudal rulers of the majority of the adjacent territory. If the

village commenced as a result -and during that era- then

perhaps his other indirect assertion could be true. Namely that the

influential Koumoutzis family, to which a majority of old

Tsintzinian families seem to hold blood or clan association,

probably dates back to them and/or is related to them. This family

held prominence in village affairs until the bloody vendetta of the

late 1800s, where their arch-rivals, the Gerasimos family

seem to prevail overwhelmingly. 3. An old School and a Hostel in Tsintzina Central Square until the late 1800s? In his unpublished 1941 Monograph about Tsintzina, Costantine Psichogios has this interesting citation: “At the western wall of the [main] church, the Cell was built, a nice building, older than the church itself, with the purpose of hosting passing poor [strangers]. Opposite the Cell [was] the old school establishment, older than the church itself but not much older than the mid-18th century. Those buildings were living history of the place during the last century of the Turks”. Psichogios cites that these buildings were recently (ie, around the turn of the 20th century) demolished, as rich emigrės from Egypt and America proposed an expansion of the village square and the old dancing floor and paid for their demolition. At the same

time, Psichogios suggests that the “centuries-old” palm trees

lining those buildings were cut. Perhaps, the five-six large palm

trees of today in the old school square and outside the church altar

were planted as a replacement at the same time. 4. St. Theodoroi Ridge Fields as a Possible Village Location. If the date c. 1330 holds true about St. John Chapel icons, then the oldest “monument” in the village itself is clearly this chapel and its the cave. A suggestion -based on a rather logical assumption- had in the past being put forward: That the initial location of the village had been just above its present place, east-southeast on a small level area which still has visible remnants of alonia but not of any housing whatsoever. One advocate of this theory was P. Dededimos, a medical doctor who, in a 1949 post to the Jamestown Lefkoma, wrote –quite assertively- that: “Tsintzina were first built at St Theodoroi fields…. [moving at] today’s location [since] 1.100 AD.”12 Dededimos does not elaborate on how he reached the conclusion of that date. He carries forward in his article to the latter periods and other facts. One wonders if he had been aware of a 1932 series of free-style interviews of Yiannis Vouloumanos (alias: Gero-Grammatikoyannis), collected by the then Goritsa schoolteacher Nikos L. Andritsakis. Another elder, “Gero-Mousklis” was also present, interjecting with his own remarks. In these interviews, Grammatikoyanis cited stories he had heard from elders that initially, Tsintzina valley was colonized by a few people who were “tsousides”. Gero-Mousklis was of the opinion that the first settlers were “zipounia” (nb: textile) makers. Grammatikoyanis remained unconvinced, noting in addition that these settlers “came and set their huts at St. Theodoroi” plains. The above elders–born circa the 1850s- were actually first-generation Goritsa-born. Elders of that era and before, have traditionally been a notable source of rather accurate and detailed information, carried forward as unwritten tradition from one generation to another.

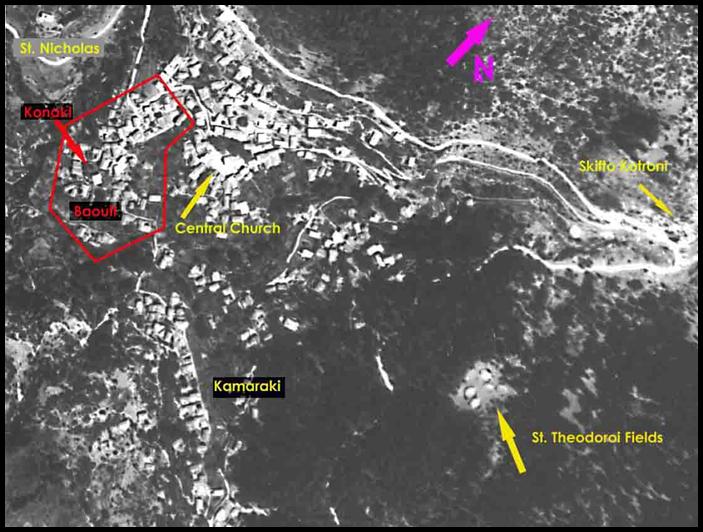

Above: 1988 aerial of Tsintzina village greater area, with St. Theodore fields clearly visible To the unsuspected, the location of St. Theodoroi would seem an obvious choice. However, this is far from an ideal place to establish a residence. First, one needs to carry water there, when in the village it comes by natural flow. Secondly, the place is shaded for most of the winter as a result of solar movement. Moreover, it is generally exposed to the elements. As Grammatikoyannis implies in his interviews, the first Tsintzinians “apparently froze out enough up there and went downhill to built houses at the ‘Konaki’ and ‘Baouti’ [areas of today’s village]” He concludes that: “seemingly [early Tsintzinians] were getting cold down there too and started crawling toward the church [area] and further [east], where they built St. Vlassis chapel”15 The creeping-expansionary path suggested by Grammatikoyannis seems quite possible on several counts of available evidence. His earlier claim of St. Theodoroi however, remains to be proven further. A common point on those who advocate a settlement at St. Theodoroi, is the name itself, suggesting a church. In his 2006 book, Dimitri Giannoukos says that the Melissinoi family (a family which held feudal estates around Tsintzina during the Frankish conquest) made a point of erecting St. Theodoroi chapels within their estates. Remnants suggesting a church however have not been clearly established.

Nothing however can be absolutely

discounted. For instance, the ruins of St. Kiriaki chapel in Goritsa

are barely visible anymore. Even if no one has suggested the

possibility of a settlement at St. Athanassios hill -a location of

equal distance to St. Theodoroi from the village to the south- such

a possibility again may not be entirely ruled out altogether. There

too, no church or other remains were ever found and no verbal

tradition ever existed. 5. The Karya Plateau. Tsintzinian K.D. Psychogios, has supported in his unpublished 1941 monograph that in the nearby Karya plateau –about 3 miles south of today’s village- a much older settlement did exist. To substantiate this, Psichogios cites evidence of low-wall ruins at the north-northwestern tip of the plateau. The area is lined up as roughly described. One is tempted to conclude however that these stone lines and limited debris, constitute rather what’s left of fencing to separate -in the familiar fashion- fields and grazing property among various owners. Psichogios accredits the presumed settlement with wealth from the trade of two kinds of commodities: Grain (wheat, maize and oats), sold to the Lakedaimona (Spartan) markets and stone and other masonry, extracted from the nearby Alevrorema corridor. Some certainty of the latter, could come from the realization that some remnants of the old Lakedaimona buildings seem to incorporate this characteristically auburn-colored stone. However, this is too weak to constitute in itself any meaningful proof. The limited area of the plateau itself –perhaps no more than ¾ of a sq. mile, would rather hardly suffice to feed the village itself. For instance, the total cultivated area to to west of the village (the one W. Leake observed in 1806) must have been of about the same size. Psichogios asserts that this settlement must have lasted until approximately the 3rd century AD. Then, the notorious raids of Alarichos ruined what was left of the Lakedaemon region. Settlers of Karya, he continues, via a path that included as intermediate stops the secluded Pilalistra and Katafi, hill summits, finally descended in Tsintzina circa 1000 AD, given the return of an overall feeling of safety and stability in the region at about that time. There, they established a craftsmen and trader’s community, as we know of Tsintzina until the 19th century. The latter

remark is certainly true. One may not be sure of the earlier points

though, until further evidence suffices to it. |